Medium-term fiscal-structural plans under the revised Stability and Growth Pact

Prepared by Othman Bouabdallah, Cristina Checherita-Westphal, Roberta De Stefani, Stephan Haroutunian, Sebastian Hauptmeier, Christian Huber, Daphne Momferatou, Philip Muggenthaler-Gerathewohl, Ralph Setzer and Nico Zorell

1 Introduction

The EU’s new economic governance framework builds on the premise that fiscal sustainability, reforms and investments are mutually reinforcing and should be fostered as part of an integrated approach.[1] Following a comprehensive reform, the revised framework – notably including the revised Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – entered into force on 30 April 2024, allowing its application as of 2025. The reformed SGP aims at ensuring sustainable fiscal positions, which are key for price stability and sustainable growth in a smoothly functioning Economic and Monetary Union. In addition, the SGP aims to balance fiscal adjustment needs with the need to enhance the implementation of productive investment and reforms, with a particular focus on strategically relevant areas such as the green and digital transitions and defence.

The submission and endorsement of the first set of national medium-term fiscal-structural plans (MFSPs) was a milestone in the implementation of the reformed economic governance framework. Last year EU Member States prepared the first set of MFSPs under the reformed economic governance framework. As a rule, such plans span four or five years, depending on the length of the national electoral cycle. In the plans, each EU Member State commits to a multi-year public net expenditure path and explains how it will deliver investments and reforms that respond to the main challenges identified in the context of the European Semester.[2] The EU’s Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN Council) endorsed the MFSPs of most Member States, issuing corresponding recommendations on 21 January 2025.[3]

In view of heightened geopolitical tensions and the need to step up defence capabilities in Europe, on 19 March 2025 the European Commission proposed a coordinated activation of the “national escape clause”. This clause had already been introduced as part of the reform of the SGP and will allow Member States to deviate – on grounds of higher defence expenditure – from the net expenditure paths set out in their MFSPs or from their corrective path under the excessive deficit procedure (EDP). If already endorsed by the ECOFIN Council, the MFSPs of the Member States will not need to be revised for additional defence spending. There is flexibility for such additional spending on defence, up to a limit of 1.5 percentage points of GDP per year over 2025-28 compared with existing fiscal commitments, in countries that choose to request the activation of the national escape clause. However, the SGP framework requires that deviations from the endorsed net expenditure paths do not endanger fiscal sustainability over the medium term. Countries which have not yet submitted plans, or the MFSP of which has not yet been endorsed, are expected to receive equivalent treatment to the other Member States when requesting activation of the national escape clause.

This article reviews the MFSPs to provide a first assessment both of the fiscal and economic implications of the reformed SGP over the short and medium term and of the implications of coordinated activation of the national escape clause. Section 2 recalls how the requirements of the reformed fiscal rules compare with the previous regime. Section 3 reviews the fiscal paths outlined in the MFSPs and assesses risks to the outlook for government debt (Box 1) as well as growth and inflation. Section 4 discusses the European Commission’s proposal to provide flexibility for defence spending within the SGP. Section 5 aims to establish whether the revised SGP will trigger additional reforms and investment, and Section 6 concludes.

2 The new fiscal rules vis-à-vis the previous regime

The new risk-based surveillance approach under the reformed SGP builds on Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) to guide fiscal adjustment paths so that government debt is brought onto a plausibly declining path by the end of an adjustment period. This period can be either four years, or up to seven if an extension is granted.[4] This approach is complemented by so-called numerical safeguards for deficit and debt reduction as well as minimum requirements when a country is subject to an EDP.[5] In June last year each Member State with a debt ratio above 60% of GDP and/or a deficit ratio above 3% of GDP in 2024 received a “reference trajectory” from the European Commission as prior guidance. Those Member States with low deficit and debt ratios received technical information, if requested. A reference trajectory spells out fiscal adjustment requirements in terms of maximum growth rates for net expenditure.[6] These are derived from the changes in the structural primary balance that underlie the DSA. The net expenditure concept serves as the single operational indicator under the revised fiscal governance framework, replacing the previous surveillance approach that built on the structural budget balance, i.e. the cyclically adjusted balance net of temporary measures. A control account will monitor deviations from these net expenditure paths, possibly triggering a debt-based EDP if cumulated deviations exceed certain numerical thresholds. [7]

Compared with the previous regime, the risk-based surveillance approach implies more differentiated fiscal adjustment requirements (Chart 1). Under the previous SGP framework, Member States had to converge towards medium-term budgetary objectives, i.e. close-to-balance underlying fiscal positions. Annual adjustment requirements were calibrated based on a “matrix approach”, accounting for cyclical conditions and the level of debt. Effectively, country differentiation was limited – despite large differences in the levels of government debt. The new approach rests on the projected evolution of public debt. Accordingly, it recognises that fiscal discipline is an intertemporal issue, implying higher adjustment requirements where debt challenges are more pronounced and/or where initial budgetary positions are less favourable. Chart 1 highlights the fact that several Member States with low indebtedness are facing very limited adjustment requirements under the revised fiscal framework – or even have room for stimulus. This holds for the requirements under the default four-year adjustment period as compared with the requirements which would have applied going forward if the previous SGP had remained in place. However, for several countries with elevated debt ratios the requirements lie mostly well above historical observed adjustments before the pandemic. In most cases the adjustments delivered were significantly lower than the average historical requirements, which were around 0.5% of GDP.

The option to extend the adjustment period from four years to seven years, in return for commitments to structural reforms and public investment, potentially provides sizeable room for fiscal manoeuvre.[8] The reformed framework recognises the medium-term benefits of productive public investment and productivity-enhancing structural reforms for fiscal sustainability. Such beneficial effects materialise via the denominator effect: higher economic growth translates into a lower debt-to-GDP ratio. Therefore, Member States can opt for an extended seven-year adjustment period if this is supported by respective policy commitments. Chart 1 shows that adjustment requirements can be reduced significantly by opting for an extended adjustment period (the blue bars indicate the average annual adjustment with an extension, while the orange bars quantify the additional adjustment that would be required in the standard four-year scenario).

Chart 1

Average fiscal adjustment over the planning period: revised versus previous SGP

(change in the structural primary balance as a percentage of potential GDP and as a percentage of GDP)

Sources: AMECO database (the annual macro-economic database of the European Commission's Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs), ECB staff calculations, the four-year and seven-year reference trajectories as obtained from the European Commission prior guidance calculation sheets published on the European Commission website, the European Commission Autumn 2024 Economic Forecast and data from the Austrian Federal Ministry of Finance. The reference trajectories are only made public upon the release of the MFSPs. In the case of Austria the data were made public by the Member State itself (for Germany and Lithuania, not shown in the chart, these data are not publicly available).

Notes: Requirements under the previous framework are calculated for 2025-28 based on the latest European Commission forecast (autumn 2024) and indicate what the required fiscal adjustment would have been under the previous framework. The calculations assume Member States under a deficit-based EDP will deliver an annual consolidation effort of 0.6% of GDP until the excessive deficit is corrected. For Member States under the preventive arm of the SGP, consolidation needs are calculated using the matrix of adjustment requirements that takes into account the debt level (higher or lower than 60% of GDP) and cyclical conditions (the level of the output gap and its variation). The consolidation is assumed to continue until the medium-term objective, in terms of structural budget balance, is reached. For more details see the “code of conduct” for the previous SGP.

3 The fiscal paths contained in the MFSPs

On 21 January 2025 the ECOFIN Council adopted the Commission’s recommendations to endorse 15 of the 16 MFSPs submitted by euro area Member States.[9] Belgium submitted its MFSP on 19 March and neither a Commission assessment nor an ECOFIN Council decision are available as yet. Three euro area countries have not yet submitted their plans, namely Germany, Lithuania and Austria.

So far, only 5 of the 17 euro area countries that have submitted MFSPs have opted for an extended adjustment period by committing to reforms and investment – though these countries represent half of the euro area economy. Specifically, Belgium, Spain, France, Italy and Finland have opted to extend the adjustment period by three years and committed to a relevant set of reforms and investments (Chart 2, panel a).

A number of euro area countries accounting for over two-fifths of euro area GDP have either not submitted a plan or are considered to lack political backing for the submitted plan, posing risks to the near-term fiscal outlook (Chart 2, panel b). Spain has submitted its MFSP, but its Parliament has not been able to pass the draft budget for 2025. Germany, Lithuania and Austria have still to submit their plans.

Chart 2

Overview of euro area countries’ MFSPs

a) Submission of MFSPs |

b) Political backing for MFSPs |

|---|---|

(percentage of euro area GDP) |

(percentage of euro area GDP) |

|

|

Sources: AMECO database, information extracted from MFSPs as published on the European Commission website and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The shares of euro area GDP are based on 2023 nominal GDP figures. Among the 17 euro area countries which have submitted their MFSPs, the following have received reference trajectories requiring them to improve their structural primary balance positions over 2025-28: Belgium, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia and Finland. Estonia and Cyprus also received reference trajectories from the European Commission, but which did not require any improvement in their structural primary balance positions. Croatia, Latvia and the Netherlands received “technical information” from the European Commission that also called for an improvement in their structural primary balance positions. This was called “technical information” and not a “reference trajectory” because the deficit-to-GDP and debt-to-GDP ratios of these countries did not exceed the respective Treaty reference values of 3% and 60%. As the deficit and debt ratios of Ireland and Luxembourg did not exceed the Treaty reference values either, these countries did not request technical information from the European Commission. The one country which is deemed not to have political backing for its plan is Spain, while Germany, Lithuania and Austria have still to submit their plans.

Several MFSPs deviate from the European Commission’s prior fiscal guidance, mostly reflecting updated budgetary and macroeconomic information. The planned cumulative net expenditure growth rates are higher than those of the Commission’s reference trajectories in most Member States, as indicated by values above the 45-degree line in Chart 3, panel a. The differences mainly relate to the fact that the initial Commission guidance had been provided to Member States on 21 June 2024, while MFSPs were only submitted later, in the autumn. By then more recent information was available on the fiscal positions in 2024 that served as the starting point for the DSA-based adjustment requirements. Updated macroeconomic assumptions were mostly assessed as duly justified by the Commission, but highlight how sensitive the new fiscal framework is to the assumptions made (see Box 1).

All Member States facing high debt sustainability risks have to plan for lower average net expenditure growth rates, also because their primary spending ratios are comparatively large. As shown in Chart 3, panel c, some of these countries record primary spending ratios of about 40% of GDP or above. Given that the net expenditure growth rates are derived from these ratios, the higher these are, the lower the expenditure growth ceilings must be to achieve the same amount of fiscal adjustment. Equally, where the fiscal efforts required are higher in terms of improvement in the structural primary balance ratio, this implies lower net expenditure growth, on average, in the MFSPs.

Chart 3

Net expenditure growth paths according to Member States’ plans

a) Cumulative net expenditure growth 2024‑28: MFSPs (y-axis) versus European Commission reference trajectories (x-axis) |

b) Differences in assumptions between MFSPs and European Commission reference trajectories |

|---|---|

(percentages) |

|

|

|

c) Average net expenditure growth for 2025-28 in MFSPs and debt sustainability risks

(x-axis: 2023 primary expenditure-to-GDP ratio, y-axis: average net expenditure growth as a percentage)

Sources: AMECO database, MFSPs and European Commission prior guidance and assessment of the MFSPs, as published on the European Commission website, and the European Commission Debt Sustainability Monitor 2023.

Notes: Panel a) shows Member States that received a reference trajectory from the Commission. Points above (below) the 45-degree line indicate countries where the cumulative net expenditure growth (from the base year 2023) in the MFSP is larger (smaller) than the corresponding cumulation of the Commission reference trajectory. Panel b) shows the differences in assumptions on the potential GDP growth rate, GDP deflator growth rate and the initial fiscal starting position for 2024. A tick indicates that the Commission concludes that the assumptions included in the MFSP are consistent with its own, while a cross indicates that the Commission’s assessment considers that there are inconsistencies. The symbols “+”, “-” and “≈” indicate whether the initial fiscal position for 2024 was more or less favourable in the MFSP than in the Commission’s reference trajectories, or broadly in line. No Commission assessment of Belgium’s MFSP was available as at the time of publication. Panel c) shows the euro area countries that have submitted an MFSP. The colour indicates the medium-term fiscal sustainability risk according to the Commission’s 2023 Debt Sustainability Monitor. Red signifies “high”, yellow “medium” and green “low” sustainability risk. For Ireland, the primary expenditure is calculated based on gross national income, which better reflects the state of the Irish economy.

The fiscal adjustment efforts in the MFSPs appear to be in line with the “no backloading” requirement in the revised economic governance framework. Chart 4 shows that the average improvement in the structural primary balance position over the first two years of the plans (2025 and 2026) is, in the vast majority of cases, either equal to or greater than the average adjustment planned for 2025‑28. This suggests that Member States do not plan to backload their fiscal adjustment to the years towards the end of the planning period.

Chart 4

Average changes in structural primary balances in the MFSPs

(percentage points of potential GDP)

Source: MFSPs as published on the European Commission website.

Notes: The chart shows the 17 euro area countries which have submitted their MFSPs. Grey bars indicate Member States with a seven-year adjustment period.

The European Commission’s Opinions on the 2025 draft budgetary plans of the euro area countries suggest, in some cases, fiscal gaps vis-à-vis the net expenditure paths contained in the MFSPs, resulting in debits on the control account. Box 1 highlights that such debits, if combined with a resetting of the account by a newly appointed government, can materially reduce the consolidation effort over the MFSP horizon. As shown above, such consolidation efforts already tend to be lower than figures derived from the Commission’s reference trajectories and their underlying assumptions. Such deviations from the reference trajectory can have tangible adverse effects on the debt trajectory, in particular for countries with high debt ratios.

Finally, before the announcements on defence spending flexibility, Eurosystem staff assessed that consolidation efforts under the revised SGP would have limited adverse macroeconomic effects overall, particularly if productive public investment is at least maintained. The macroeconomic implications of the consolidation needs under the revised EU framework are relevant for a comprehensive assessment of the new SGP rules. A preliminary analysis in early 2024, before countries started submitting MFSPs, found that abiding fully by the SGP consolidation requirements would imply some short-term downside risks to growth at the euro area level and muted effects on inflation.[10] An updated analysis for the period 2025-27, as part of the 2024 December Eurosystem staff projections, takes into account the new information in the MFSPs and the 2025 draft budgetary plans. In particular, it incorporates the chosen adjustment periods and the planned structural efforts. It broadly confirms the previous assessment of limited adverse macroeconomic effects.[11] Some of the measures outlined in the government plans – those measures well specified – were included in the December baseline projections. Overall this induced slight revisions to the baseline growth and inflation projections.[12] The estimated macroeconomic and fiscal effects are surrounded by uncertainty. This is especially the case for those countries which have not yet submitted an MFSP or where the plan is already outdated. Another source of uncertainty is the potentially different composition of the consolidation ultimately implemented by governments. Moreover, in the absence of fiscal adjustment, confidence effects may play an important role – especially in the high-debt countries. Finally, the additional potential defence spending allowed under the rules in the context of heightened geopolitical tensions has increased the uncertainty surrounding the outlook for economic growth and inflation in the euro area. An increase in defence and infrastructure spending could add to growth and also raise inflation through its effect on aggregate demand.[13]

4 Flexibility for defence spending

Following the endorsement of the MFSPs of most EU Member States by the ECOFIN Council and in light of geopolitical developments, in March 2025 the European Commission proposed the coordinated activation of the national escape clause under the SGP. This was part of the European Commission’s ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030, as announced on 19 March 2025.[14] In early March EU leaders had welcomed the Commission’s stated intention to recommend that the Council activate, in a coordinated manner, the national escape clause under the SGP. The Commission was also called on to explore further measures to facilitate significant defence spending at national level in all Member States while ensuring debt sustainability.[15] It provided greater detail on the implementation of the national escape clause in a Communication published on 19 March.

The Commission will activate the national escape clause in the SGP on grounds of exceptional circumstances outside the control of Member States, which has important implications for the implementation of the MFSPs. Specifically, Member States will need to submit their requests by the end of April. Activating the clause allows a Member State to deviate from its net expenditure path as set by the ECOFIN Council or from the corrective path under the EDP, provided that such deviation does not endanger fiscal sustainability over the medium term. The budgetary flexibility for Member States activating this clause will be granted on two conditions. First, there will be a cap of 1.5% of GDP on additional spending per year for 2025-28 – for each Member State irrespective of its distance to/from NATO’s 2% of GDP target for defence expenditure. Any increases beyond that cap will be subject to the usual assessments of compliance. Second, the additional fiscal space is to be used for extra defence expenditures and is to include both investment and current expenditure.[16] The increase in defence expenditure covered by flexibility under the national escape clause will be calculated relative to 2021 – the reference year. After 2028, Member States will have to sustain the higher spending level through gradual reprioritisation within their national budgets in order to safeguard fiscal sustainability.

Apart from the flexibility granted for defence spending, the fiscal framework should continue to operate normally. Concretely, the net expenditure growth ceilings of Member States as set out in their MFSPs remain valid. This implies that EU fiscal surveillance will monitor countries’ compliance with the net expenditure paths included in the national plans and – where applicable – the EDP recommendations. The assessment of compliance with agreed spending ceilings is, however, to be conducted in a way that nets out the amount of defence spending subject to the escape clause. Therefore, in the absence of compensatory measures, debt trajectories would deviate from those projected at the time of endorsement. The implications of the triggering of national escape clauses for additional defence spending are analysed in Box 1.

Box 1

Flexibility in the reformed EU governance framework: implications for government debt

This box conducts a sensitivity analysis of the different sources of flexibility under the revised governance framework. It quantifies the associated risks for the evolution of government debt that may result from: (i) deviations of the macroeconomic assumptions underlying the MFSPs from the commonly agreed assumptions set out in the prior guidance from the European Commission; (ii) deviations from the fiscal path arising from “debits” accruing in the control account; and (iii) the possibility of a control account being reset if a new government is appointed.

Since the only reference trajectories publicly available from the European Commission are based on its Spring 2024 forecast, this analysis first includes ECB staff recalculations of adjustment requirements, using the Commission’s Autumn 2024 forecast. The aim is to start the analysis from the latest projections and to assess the impact of the updated starting fiscal position (2024) and the macro-financial environment. Scenario 1 (S1) illustrates the debt implications of fully meeting these updated requirements. Scenario 2 (S2) presents the debt trajectories based on the fiscal path outlined in the MFSP, but using the S1 macroeconomic and financial assumptions. As the fiscal path outlined in the MFSP in most countries is derived from a different set of assumptions (see Section 3), the difference between S1 and S2 highlights the debt implication of such deviations. A third scenario (S3) assumes that the country deviates from the initial trajectory set in the MFSP but without breaching a maximum of 0.6 percentage points of GDP cumulatively over the expected term of each government. Breaching this maximum is referred to in the revised Regulation as the basis for enforcement action.[17] While the scenario does not incorporate any assessment of the likelihood of this, it aims to capture a lower bound to the adjustment path and its implications for debt. Compared with the baseline scenario (S1), the two alternative scenarios explore different fiscal paths over the selected adjustment period, aiming to quantify the impact of deviations from full compliance under revised assumptions. To ensure a meaningful comparison, all three scenarios incorporate one update of the adjustment plan after four years, as envisaged in the Regulation.

The simulations show that the more optimistic assumptions used by some governments in their MFSPs have a limited overall impact on debt dynamics (Chart A, blue and yellow lines). A closer examination of the underlying factors reveals that the safeguards in the new framework, which complement the fiscal requirements derived from the DSA, generally prevent significant reductions in fiscal requirements compared with the initial reference trajectory. However, debits accruing on the control account and/or a resetting of this account each time a new government is appointed could materially reduce the cumulated consolidation effort over the MFSP horizon (Chart A, red line).[18] For high-debt euro area economies, the adverse effects of deviating from the reference trajectory could be substantial. Assuming that the adjustment plans are updated in all three scenarios after four years, the simulations show that the deviation could lead to less favourable dynamics and higher debt ratios – up by more than ten percentage points over ten years in S3 – and potentially also higher financing costs. The impact on the low-debt countries is somewhat smaller; and the aggregate debt ratio would remain below the Treaty’s 60% reference value under S3. The framework seems to prevent the accumulation of additional sovereign debt. However, the possibility of persistent deviations envisaged in the Regulation suggests that failure to fully implement the initial requirements in a timely manner will not necessarily require more substantial fiscal consolidation measures in the future. Rather, it would merely facilitate debt stabilisation at the current elevated levels, preventing a more significant reduction of the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Chart A

Debt outlook under different fiscal scenarios

a) Aggregate for high-debt countries

(percentage of GDP)

b) Low-debt countries’ aggregate

(percentage of GDP)

Sources: ECB staff calculations, based on the European Commission’s 2024 Autumn Forecast.

Notes: Countries with government debt ratios higher than 90% in 2023 are included in the “high-debt” group (Belgium, Greece, Spain, France, Italy and Portugal). The updated reference trajectories assume an adjustment period for each Member State aligned with that chosen in its MFSP. For the Netherlands, in line with the Commission’s recommendation, we use the required consolidation path as set out in the June 2024 reference trajectory. Among the countries that had not submitted a MFSP by the time this article was finalised (Germany, Lithuania and Austria), a seven-year adjustment period is assumed for Germany. The benchmark revisions of national accounts have on average made the requirements slightly more demanding compared with the June 2024 trajectories based on the Commission’s Spring Forecast. S2 uses the fiscal adjustment paths outlined in the MFSPs along with the macroeconomic and financial assumptions from S1. S3 assumes, cumulatively, a deviation (from S2) of 0.6 percentage points of GDP over two consecutive years at the start of the adjustment period (2025 and 2026). It also assumes an additional deviation if a new election is scheduled during the adjustment period. After four years, the updated reference trajectories are updated, assuming full compliance over the second cycle for S1 and S2 and continuous deviation for S3.

Turning to the impact of activating the national escape clause on the debt outlook, we assume that the clause is activated in a coordinated manner. It thereby allows each Member State to gradually increase defence spending by 1.5% of GDP, the maximum allowed, over a period of four years. In addition, Member States for which the debt and deficit safeguards were binding when defining the consolidation requirements will be exempted from this clause and can therefore further increase their spending beyond the standard 1.5% ceiling. Although flexibility on defence spending operates alongside the control account, and both mechanisms can contribute to additional fiscal space, this analysis focuses solely on the impact of the national escape clause on debt accumulation. As with the control account assessment, we reflect on the Commission’s update of fiscal requirements at the end of the first planning period. We therefore quantify the likely increase in consolidation requirements to offset the initial increase in spending.

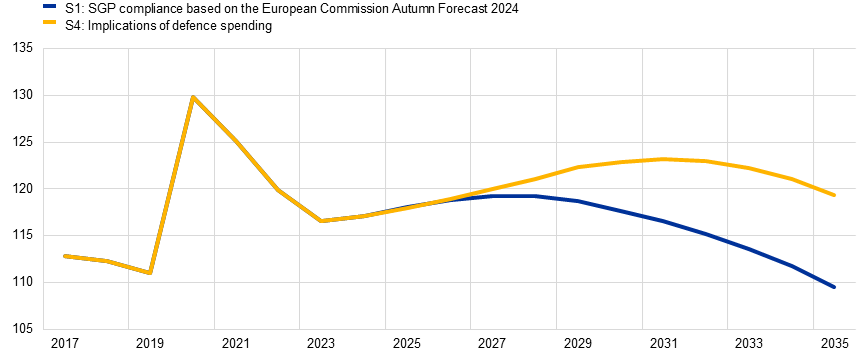

Chart B illustrates the aggregate impact on high-debt countries, showing how the national escape clause could affect their debt trajectory. Scenario 4 (S4) is the activation of the national escape clause for four years, with additional spending phased in gradually and linearly to reach the 1.5% of GDP ceiling by the end of the period for all countries. This would reduce the overall fiscal adjustment for high-debt countries by about 1.7 percentage points compared with the agreed medium-term fiscal plans. This would lead, initially, to a worsening of debt dynamics. Even if the escape clause were to be fully utilised, the envisaged full compliance with the requirements of the SGP in the second planning period, starting in 2029, would ensure that debt returns to a declining path (Chart B, panel a). This would shift the sizeable fiscal adjustment from the first to the second planning period (Chart B, panel b). Importantly, this scenario and its debt implications remain purely illustrative, as they rest on two strong assumptions. First, they assume a coordinated activation of the national escape clause and the gradual and linear financing of additional defence spending of 1.5% of GDP over 2025-28. Second, they assume all financing takes place through national debt issuance.[19]

Chart B

Implications of maximum SGP flexibility for defence spending in high-debt countries

a) Debt evolution

(percentage of GDP)

b) Required fiscal adjustment

(percentage of GDP)

Sources: ECB staff calculations, based on the European Commission’s 2024 Autumn Forecast.

Notes: Countries with government debt ratios higher than 90% in 2023 are included in the “high-debt” group (Belgium, Greece, Spain, France, Italy and Portugal). The updated reference trajectories assume an adjustment period for each Member State aligned with that chosen in its MFSP. For the Netherlands, in line with the Commission’s recommendation, we use the required consolidation path as set out in the June reference trajectory. Among the countries that had not yet submitted an MFSP (Germany, Lithuania and Austria), a seven-year adjustment period is assumed for Germany. S4 assumes, cumulatively, a deviation (from S1) of 1.5% of GDP over four consecutive years (2025-28) and an additional deviation resulting from the exemption for the debt and deficit safeguard. After four years, the reference trajectories are updated, assuming full compliance over the second cycle for both S1 and S4.

5 Public investment and structural reform commitments

Another key design feature of the revised governance framework is its aim of fostering productive investment and growth-enhancing reforms.[20] Member States opting for an extension need to make sure that the planned level of nationally financed public investment is no lower during the MFSP period than its previous medium-term level. The European Commission operationalises this by comparing the average ratio to GDP of nationally financed public investment over the planning period with the average level over the period covered by the respective Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), i.e. 2021/22 to 2026. In its assessments of the MFSPs, the Commission finds that four euro area countries that have opted for an extension of the adjustment period so far meet the condition (Spain, France, Italy and Finland).[21] The revised rules require that countries seeking an extension of their fiscal adjustment period commit to a set of adequate reforms, thereby increasing reform incentives. These reforms should respond to the main policy challenges identified in the context of the European Semester. Ultimately, the reforms in the national plans should lead to higher potential output growth and thereby reduce fiscal adjustment needs.

Nationally financed public investment is planned to remain at or above average pre-pandemic levels in all five euro area countries that opted for an extended adjustment period. Chart 5 compares nationally financed government investments as a percentage of GDP over 2025-28 with the average for 2014-19. This average can provide additional insights relative to the Commission’s operationalisation, because the period concerned was not affected by the large investments foreseen in the RRPs. The national plans for Belgium, Spain, Italy and Finland aim at reaching a level of nationally financed government investment that is, on average, significantly above the 2014-19 average. Only the French plan maintains nationally financed government investment broadly at the levels observed in 2014-19. Public investment commitments in the MFSPs appear to mostly overlap or complement existing measures included in the RRPs. In Iine with the revised economic governance framework, the Commission assesses these as addressing the common priorities of the EU, including the green and digital transitions.

Chart 5

Average nationally financed government investment according to the MFSPs for 2025-28 versus 2014-19

(percentage of GDP)

Sources: AMECO database and European Commission assessments of the MFSPs, as published on the European Commission website. The European Commission’s assessment of the Belgian MFSP was not yet available, therefore the average nationally financed government investment figure is the one reported in the MFSP.

Notes: The chart focuses on the four euro area countries which have requested an extension of the adjustment period from four to seven years. For 2014-19 the nationally financed government investments are defined as the gross fixed capital formation series from which EU capital transfers are deducted.

The reforms supporting an extension of the adjustment period focus mainly on the public sector. The plans of the five euro area countries seeking an extension of the adjustment period include 71 extension-related reforms. Half of them can be broadly categorised as public sector reforms, for instance aiming to enhance tax administration or the judiciary (Chart 6). Labour market, education and social policies account for around one-fifth of all planned reforms. The categories “business environment” and “green/digital framework conditions” account for 15% and 12%, respectively. The remaining reforms are related to financial policies (4%), most notably insolvency frameworks and the housing market. With its focus on public sector reforms, the reform mix in the fiscal-structural plans is therefore comparable to that envisaged by the RRPs.[22]

Chart 6

Reforms in countries seeking an extension of the adjustment period: policy areas

(percentage of overall number of reforms)

Source: ECB aggregation based on MFSPs.

Notes: Includes the five euro area countries seeking an extension of the adjustment period (i.e. Belgium, Spain, France, Italy and Finland). The classification is based on an ECB staff assessment and only covers the reforms underpinning the requested extension. “R&I” stands for research and innovation.

Most of the planned reforms are either already included in the RRPs or designed to complement them. While the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is in operation, the revised governance framework allows Member States to include in their MFSPs reforms that have already been implemented or planned in the context of the RRPs. Some 37% of the reforms underpinning an extension of the adjustment period fall into this category (Chart 7). Another 37% of the relevant reforms are designed to complement or extend those set out in the RRPs. The remaining 26% can be seen as new, stand-alone reforms without a direct connection to the RRPs, such as the planned streamlining and improvement of the efficiency of state-owned enterprises in Italy.

Chart 7

Reforms in countries seeking an extension of the adjustment period: RRP links

(percentage of overall number of reforms)

Source: ECB aggregation based on MFSPs.

Notes: The classification is based on the European Commission’s assessment and only covers the reforms underpinning the requested extension. It includes the euro area countries seeking an extension of the adjustment period, except Belgium, for which no European Commission assessment was available as at the cut-off date for this publication.

The growth impact of the suggested reforms is difficult to assess. First, there is no agreed methodology for determining the potential quantitative impact of reforms on the fiscal adjustment required under the new rules.[23] Among the five euro area countries seeking an extension of the adjustment period, only Spain and Italy provide comprehensive estimates of the expected growth impact that, though not comparable, are based on specific models or comparisons with baseline scenarios. Second, so far the reforms are only public commitments – important parameters concerning the design and implementation of the reforms are still to be decided. Therefore, the overall impact on potential output growth is hard to quantify.

6 Conclusion

The implementation of the reformed economic governance framework is surrounded by significant uncertainty. Although fiscal surveillance under the SGP framework is envisaged to continue to operate normally, it needs to take into account a coordinated activation of the national escape clause of the SGP. Such activation also follows a prolonged period (2020-23) in which the general escape clause of the SGP had already been activated, implying a de facto suspension of the European fiscal rules. In addition to challenges related to the escape clause, the uncertainty relates to the fact that some countries have yet to submit a plan or their plan lacks political backing. Moreover, future plans will need to rest on prior guidance from the European Commission based on more recent forecasts, factoring in recent shifts in the political and economic context. Overall, the course of fiscal policy in the euro area in 2025 and beyond remains surrounded by high uncertainty, not least as Member States still have to spell out their plans regarding defence.

In view of high uncertainty, full implementation of the commitments undertaken in Member States’ MFSPs is crucial. As the SGP rules continue to be implemented, Member States should fully implement their fiscal and structural commitments as this will also help limit the deficit and debt-increasing impact of additional spending on defence. Fiscal consolidation measures need to be well-designed, and accompanied by growth-enhancing reforms and public investment, to limit adverse macroeconomic effects through aggregate demand. And the latter would in part be offset by confidence effects, notably in high-debt countries.

The national escape clause needs to be implemented in a targeted way, that ensures a rise in defence spending while preserving medium-term fiscal sustainability in line with the requirements of the SGP. In this context, it is essential that flexibility to deviate from an endorsed net expenditure path is only used for the necessary additional defence spending, as envisaged by the Commission in its Communication. This will be important to preserve the credibility of the recently reformed EU fiscal framework, thus achieving the defence spending goals without endangering medium-term fiscal sustainability. Deviations from the net expenditure paths should continue to be recorded in order to ensure normal surveillance of compliance with the commitments in the plans.

Appropriate surveillance and monitoring of fiscal adjustment, reform and investment commitments will be crucial to ensure that the objectives of the revised fiscal and economic governance framework are met. The framework builds on the premise that fiscal sustainability, reforms and investment are mutually reinforcing and should therefore be fostered as part of an integrated approach. ECB staff estimates suggest that gaps in the fiscal adjustment vis-à-vis the net expenditure ceilings of the MFSPs could emerge in the near term. Such gaps – if sizeable and persistent – may interfere with the objective of the new framework, namely putting debt on a plausibly declining path over the medium term, especially in view of the need for additional spending on defence. It is important that Member States do not use the flexibility offered by the control account ex ante, this being intended to be used to monitor deviations from agreed consolidation paths rather than provide additional fiscal space. Going forward, proper surveillance of the implementation of the plans will be crucial to ensure that the comprehensive new governance framework gains credibility and delivers on its stated objectives from the start.

Finally, the plan’s reform and investment initiatives will need to be implemented effectively. It will be essential to sustain national public investment, in line with the commitments contained in the MFSPs, in order to also address challenges in strategic areas other than defence, such as the green and digital transitions. Member States’ plans also contain important reform initiatives, which significantly overlap with or complement existing commitments under the Next Generation EU programme. The reforms and investments, if well implemented, can raise potential growth, thereby providing an important contribution to the sustainability of public finances. If anything, the most recent challenges that Europe has been confronted with have strengthened the case for stepping up efforts to bring about sustainably higher economic growth.

Distribution channels: Banking, Finance & Investment Industry

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release